By Avril Groom

A decade ago, ethical and sustainable fashion was a minority interest in a world dominated on one side by high-end luxury apparently unconcerned with such matters, and on the other by fast fashion driven by cheap, quick production. Opinion formers found it hard to shake off suspicions that ethical fashion meant shapeless oatmeal tunics and hairy hand-knits. How times change.

Events like the Rana Plaza building collapse in 2013, which killed more than a thousand Bangladeshi garment workers, lifted an uncomfortable lid on dreadful working conditions.

At the top end, the work of people like Stella McCartney, with her commitment to beautiful, vegan and – where possible – environmentally sustainable fashion, Eco-Age founder Livia Firth who campaigns on both environmental and humanitarian fronts and whose film The True Cost reveals shocking facts about the global clothing industry, and Vivienne Westwood who has long used organic cotton, artisan wools and works with African women’s groups on production, have caused many consumers to re-examine their values.

Today’s millennial generation is very aware of world problems and seeks authenticity and sustainability as a matter of course, and as a result ethical and sustainable fashion is building a head of steam. “Millennials are not just into selfies, they are well informed, care about working conditions and environmental degradation and are prepared to pay a little more for the right brand values,” says Alicia Taylor, co-founder of ethical fashion website Gather and See. “They pick up on reports of injustices in the industry and campaigns like #FashionRevolution encourage consumers to question ethical practices – authenticity and transparency are now important to brands’ DNA. People can be confused by terminology because there are different ways to be sustainable, so we explain each brand’s philosophy – organic materials, fair trade, upcycling or small-scale local production and sometimes several of those.”

Two high-profile events have focused the public eye on sustainability. Last September’s first Green Carpet Fashion Awards, a glamorous event at La Scala in Milan masterminded by Firth, honoured sustainability conscious brands, mostly Italian as this is the stronghold of artisan craft, where sustainability comes naturally to brands like menswear giant Zegna, which created forest parks for their workers’ enjoyment half a century ago, or Brunello Cucinelli, a farmer’s son to whom respect for community and environment is second nature in every aspect of his luxury cashmere brand. Small-scale winners included Chiara Vigo, the last known weaver of sea silk (a super-delicate yarn produced by live clams), a firm which makes fabrics from waste orange pith, and Emerging Sustainable Designer winner Tiziano Guardini, who works with organic silk, recycled nylon and sequins made from seashells and waste CDs.

However, just as they have lagged at adopting online commerce, big luxury brands are slow on sustainability, with the exception of the Kering Group, which has its own director in this area and until recently had McCartney as its trailblazer – she is now independent. Even the recent move by a number of top brands to ban real fur is controversial; because of its plastics base, fake fur is far less disposable than real and although some is now made from recycled materials, it can hardly be regarded as sustainable.

Among big firms, the high street has a better record than luxury brands, with mid-market plastics recycling brand Patagonia founded 45 years ago, and Eileen Fisher more than 30 years ago, both on sustainable principles, H&M’s Conscious range, Mango’s Committed collection and ambitious Take Action plan, and Marks & Spencer’s Plan A (both to reduce environmental impact). But, increasingly, smaller brands at both luxury and moderate levels are taking the initiative, with young designers whose belief in sustainability is fundamental.

Gabriela Hearst’s high luxe range includes merino wool from sheep raised on her Uruguay farm, organic linen woven with natural aloe for an extra smooth, silky finish, and hand-painted, natural leather shoes. Polish designer Monika Kędziora of Acephala is a feminist activist but her embroidered slogan T-shirts and beautiful, full-sleeved shirts are made from the best organic cotton, while the minimalist, Japanese-influenced shapes by Oyuna are made in Mongolia from vegetable-dyed cashmere produced by the designer’s family herds. The Berlin-based duo behind Kemp Gadegaard believe in timeless, slow fashion where organic silk, bamboo and cotton is worked in small-scale, European production to create an add-to wardrobe.

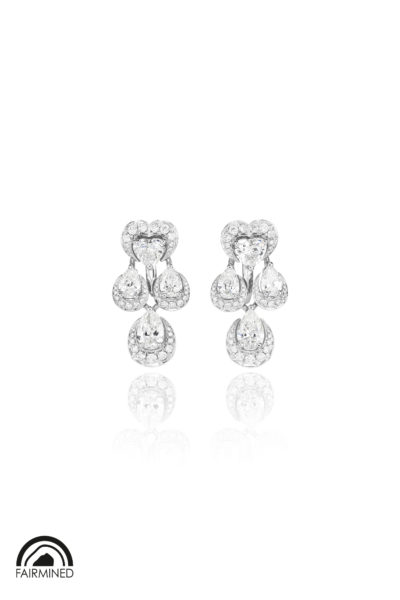

Sustainable accessories are an even more thriving area. The success of French sneaker brand Veja, which works with indigenous and artisan people in Brazil and includes wild rubber, natural silk and fabric from recycled plastic in its styles, is big news. Well-designed bags made from vegan materials, from brands such as Matt and Nak or M2 Malletier, are much sought after. Sustainable jewellery is a hive of activity, from a growing list of brands working with traceable, ethically sourced materials to designers like Lilian von Trapp, who works only with recycled gold – melted down and re-alloyed to her colour specifications – for delicate, geometric pieces that mix, match and stack.

Specialist websites help such designers. In addition to Gather&See, known for year-round holiday wear, chic, easy pieces and affordable, interesting jewellery, there is The Acey for good working clothes, organic lingerie and jewellery, and Reve en Vert’s sophisticated style including smart dresses and active wear. They all continually seek new designers to feed today’s consumer desire for individuality, a task that has become easier. “We have seen a huge increase in ethical brands approaching us to stock them, which is a very positive indicator,” says Taylor. “Young designers are building sustainability into their production from the beginning.” The whole industry doing the same no longer seems such a pipedream.

The post Slow down appeared first on JFW MAGAZINE.